Efforts like Kepler to find Earth-like planets outside our galaxy may have ended recently, but astronomers say a wave of bigger and better missions is on its way.

As mountains go, Cerro Armazones may not be much to look at. Standing 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) tall, it is a shapeless reddish dust heap in Chile’s hot and arid Atacama Desert. The only sign of life is a dirt road zig-zagging all the way to the top.

But for astronomers like Joe Liske, this is arguably the world’s most interesting mountain right now, and not just because in the next few months more than 100 tons of dynamite will blow off its top to create a flat platform. By the early 2020s, that platform will become home to the biggest-ever eye on the sky, the E-ELT, or European Extremely Large Telescope.

With a mirror that is 39 meters (128ft) in diameter, the E-ELT will dwarf all existing optical telescopes – and those planned to appear in the next decade or two. And it won’t just bring plenty of life to this corner of the Atacama. The hope is that it will also help spot life out in the vastness of space.

In the past decade alone, astronomers have been discovering planets outside our solar system, or exoplanets, with astonishing speed. We now have identified nearly a thousand. Most are much bigger than Earth and almost certainly Jupiter-like gas giants, making them quite unlikely for hosting life. None has so far been confirmed to bear life – even single-cell organisms – but some of these planets seem to be distinctly rocky and Earth-like: Kepler-62e, Gliese-581g and Kepler-22b, to name a few.

“The quest for Earth-like exoplanets, and ultimately life on such planets, is one of the great frontiers of science, perhaps the last big piece in the puzzle of how we, humans, fit into the big picture,” says Liske, who works at the European Southern Observatory, an organization that already operates a number of telescopes in the Chilean desert.

Two of the more high-profile planet hunters have hit rocky ground in recent months, however. The French-led Corot spacecraft, launched in 2006, greatly outlived its original two-and-a-half year mission of spotting terrestrial-sized exoplanets, but in November 2012, it suffered a computer malfunction, which made it impossible to send any data back to Earth. In June 2013, the French Space Agency announced it would switch the satellite off and let it burn up as it re-enters the atmosphere – the usual fate of our mechanical helpers in space.

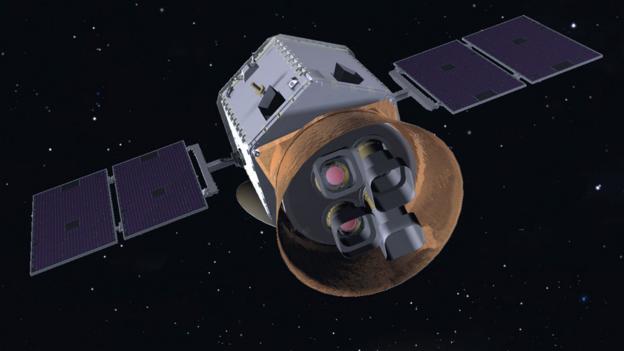

Nasa’s $600 million space observatory Kepler, launched in 2009, has also been crippled recently. Kepler has helped spot thousands of potential exoplanets – over 130 of which have been confirmed – but two of its four reaction wheels that control the telescope’s direction have failed in recent months, and at least three are necessary to point it in the right direction. Kepler completed its primary mission in November 2012, and there are still thousands of candidates to sift through, but this month Nasa conceded that Kepler will no longer be able to search for exoplanets.

Size matters

To be considered a “habitable” world, a planet has to be similar to Earth in size, rocky, and located in the so-called Goldilocks zone – an area of space around a parent star that is not too cold or too hot, but just right to support liquid water. Since these planets are expected to be small and faint compared to their sun, spotting them is tricky with existing ground-based optical telescopes.

To tell a parent star and a potentially habitable planet apart, astronomers need incredibly sharp, high-resolution pictures. The bigger the mirror, the sharper the image a telescope can capture, and the dimmer the objects it can detect. Hence it takes an extremely large telescope to try to spot any planets that may support alien life many light years away.

“With the E-ELT, we believe that we will be able to directly see exoplanets similar to Earth out to a distance of about 20 light years,” says Liske.

The closest potentially habitable planet is about seven light years away, according to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Hubble Space Telescope has been circling Earth since 1990 and has spotted a few planets – and also helped determine what some extra-solar worlds are probably made of. But Hubble’s 2.4m (7.9ft) mirror is too small to see planets smaller than Jupiter, says Matt Mountain, the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute at Nasa. Hubble’s planned successor, the James Webb Space Telescope(JWST) – set to go into orbit around 2018 – is expected to do much more. It will work in the infrared spectrum, which will allow it to “probe down to smaller planetary sizes than Hubble, to roughly two-to-three times larger than Earth, more Neptune-scale planets,” says Mountain.

The telescope will aim to find out whether these extra-solar worlds are so-called “super-Earths” – rocky planets that could potentially be habitable – or miniature versions of Neptune, unable to support life. Using an instrument called a coronagraph, JWST will try to determine whether a planet has an atmosphere, and – for the first time – analyze it by examining the spectrum of the light coming from the planet. Elements and molecules in an atmosphere, such as water and oxygen, have specific signatures in the spectrum, giving us an idea about its composition and the likelihood that there is liquid water present – and hence life, says Avi Loeb, Chair of the Astronomy department at Harvard University.

But to really find a habitable Earth-twin orbiting a star just like our Sun, we will have to go to space, he adds – with a giant telescope fully designed for planet hunting and equipped with a mirror of eight metres or more. That won’t happen any time soon – but Nasa is already thinking about a future replacement, called the Advanced Technology Large Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST), a space telescope with a 8-to-16m mirror that would be 2,000 times more light-sensitive than Hubble. If all goes according to plan, ATLAST could be launched between 2025 and 2035.

The fact that there have been few good candidates for planets that host life found so far should not discourage the searchers. The data already collected suggests that there are about 100 billion planetary systems in our galaxy alone, says Mountain. So there are plenty of places left to look, as and when we find the tools for the task.

But for astronomers like Joe Liske, this is arguably the world’s most interesting mountain right now, and not just because in the next few months more than 100 tons of dynamite will blow off its top to create a flat platform. By the early 2020s, that platform will become home to the biggest-ever eye on the sky, the E-ELT, or European Extremely Large Telescope.

With a mirror that is 39 meters (128ft) in diameter, the E-ELT will dwarf all existing optical telescopes – and those planned to appear in the next decade or two. And it won’t just bring plenty of life to this corner of the Atacama. The hope is that it will also help spot life out in the vastness of space.

In the past decade alone, astronomers have been discovering planets outside our solar system, or exoplanets, with astonishing speed. We now have identified nearly a thousand. Most are much bigger than Earth and almost certainly Jupiter-like gas giants, making them quite unlikely for hosting life. None has so far been confirmed to bear life – even single-cell organisms – but some of these planets seem to be distinctly rocky and Earth-like: Kepler-62e, Gliese-581g and Kepler-22b, to name a few.

“The quest for Earth-like exoplanets, and ultimately life on such planets, is one of the great frontiers of science, perhaps the last big piece in the puzzle of how we, humans, fit into the big picture,” says Liske, who works at the European Southern Observatory, an organization that already operates a number of telescopes in the Chilean desert.

Two of the more high-profile planet hunters have hit rocky ground in recent months, however. The French-led Corot spacecraft, launched in 2006, greatly outlived its original two-and-a-half year mission of spotting terrestrial-sized exoplanets, but in November 2012, it suffered a computer malfunction, which made it impossible to send any data back to Earth. In June 2013, the French Space Agency announced it would switch the satellite off and let it burn up as it re-enters the atmosphere – the usual fate of our mechanical helpers in space.

Nasa’s $600 million space observatory Kepler, launched in 2009, has also been crippled recently. Kepler has helped spot thousands of potential exoplanets – over 130 of which have been confirmed – but two of its four reaction wheels that control the telescope’s direction have failed in recent months, and at least three are necessary to point it in the right direction. Kepler completed its primary mission in November 2012, and there are still thousands of candidates to sift through, but this month Nasa conceded that Kepler will no longer be able to search for exoplanets.

Size matters

To be considered a “habitable” world, a planet has to be similar to Earth in size, rocky, and located in the so-called Goldilocks zone – an area of space around a parent star that is not too cold or too hot, but just right to support liquid water. Since these planets are expected to be small and faint compared to their sun, spotting them is tricky with existing ground-based optical telescopes.

To tell a parent star and a potentially habitable planet apart, astronomers need incredibly sharp, high-resolution pictures. The bigger the mirror, the sharper the image a telescope can capture, and the dimmer the objects it can detect. Hence it takes an extremely large telescope to try to spot any planets that may support alien life many light years away.

“With the E-ELT, we believe that we will be able to directly see exoplanets similar to Earth out to a distance of about 20 light years,” says Liske.

The closest potentially habitable planet is about seven light years away, according to the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

The Hubble Space Telescope has been circling Earth since 1990 and has spotted a few planets – and also helped determine what some extra-solar worlds are probably made of. But Hubble’s 2.4m (7.9ft) mirror is too small to see planets smaller than Jupiter, says Matt Mountain, the director of the Space Telescope Science Institute at Nasa. Hubble’s planned successor, the James Webb Space Telescope(JWST) – set to go into orbit around 2018 – is expected to do much more. It will work in the infrared spectrum, which will allow it to “probe down to smaller planetary sizes than Hubble, to roughly two-to-three times larger than Earth, more Neptune-scale planets,” says Mountain.

The telescope will aim to find out whether these extra-solar worlds are so-called “super-Earths” – rocky planets that could potentially be habitable – or miniature versions of Neptune, unable to support life. Using an instrument called a coronagraph, JWST will try to determine whether a planet has an atmosphere, and – for the first time – analyze it by examining the spectrum of the light coming from the planet. Elements and molecules in an atmosphere, such as water and oxygen, have specific signatures in the spectrum, giving us an idea about its composition and the likelihood that there is liquid water present – and hence life, says Avi Loeb, Chair of the Astronomy department at Harvard University.

But to really find a habitable Earth-twin orbiting a star just like our Sun, we will have to go to space, he adds – with a giant telescope fully designed for planet hunting and equipped with a mirror of eight metres or more. That won’t happen any time soon – but Nasa is already thinking about a future replacement, called the Advanced Technology Large Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST), a space telescope with a 8-to-16m mirror that would be 2,000 times more light-sensitive than Hubble. If all goes according to plan, ATLAST could be launched between 2025 and 2035.

The fact that there have been few good candidates for planets that host life found so far should not discourage the searchers. The data already collected suggests that there are about 100 billion planetary systems in our galaxy alone, says Mountain. So there are plenty of places left to look, as and when we find the tools for the task.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Through this ever open gate

None come too early

None too late

Thanks for dropping in ... the PICs